Daesh’s Image-Weaponry in the Battle for Mosul

archive

Daesh’s Image-Weaponry in the Battle for Mosul

On July 10, 2017, the Iraqi PM announced the liberation of the Daesh stronghold of Mosul after about nine months of fighting. The battle, however, was not limited to military action since Daesh was also waging war on the social media battlefield by visualizing the group’s resilience to its online followers, supporters, and fanboys. Daesh was in a quite similar position in 2007-2009 as the surge of U.S. troops in Iraq along with Sunni tribal resistance rolled back the group’s physical presence, yet it managed to maintain an online presence and boost its statehood claims by declaring two ministry cabinets. Over the years, the group has successfully built a relatively robust propaganda infrastructure capable of disseminating content and promoting “Media Jihad” as equivalent to fighting in battle. The Mosul Operation posed a unique opportunity to gauge the extent to which Daesh could sustain a virtual warfare campaign under immense military pressure.

Studies analyzing Daesh’s propaganda over the past three years show that still photographic imagery plays an integral role in Daesh’s propaganda mix.1 Daesh disseminates its imagery in provincial photo reports and multi-lingual publications. Studies examining Daesh’s visual propaganda mainly focus on the group’s English-language magazine, Dabiq. Some researchers have compared Dabiq to Rumiyah and al-Qaeda’s Inspire magazine,2 while others have traced the origin of Dabiq imagery, analyzed the about-to-die visual trope,3 and categorized images by visual frames and/or purpose.4 The existing literature lacks analyses of Daesh’s imagery at the provincial level and the pictorial conventions it incorporates, including subjective-camera shots, camera angles, direct eye contact, and viewer distance. In this essay, I present preliminary findings of a content and visual framing analysis of images disseminated by Ninawa Province from the beginning of the operation on October 17, 2016 to the end of January 2017, when east Mosul was liberated.

Daesh’s Image-Weaponry

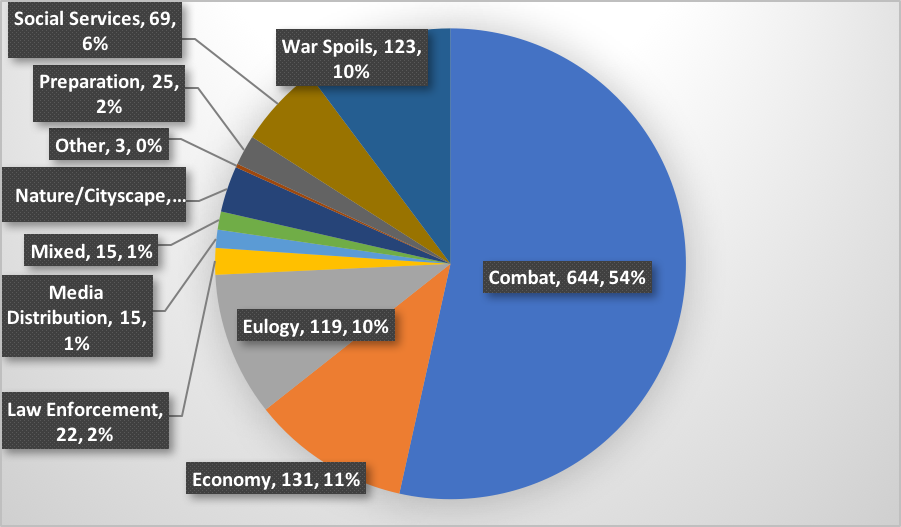

Daesh’s Ninawa Province disseminated a total of 1204 images, increasing from an average of 10 per day in late October to 14 per day in November and December, before dropping to seven per day in January. This imagery can be sorted into two main categories of military and non-military, which together are comprised of eight visual frames: combat, preparation, eulogy, law enforcement, social services, economy, natural landscape/cityscape, and media distribution. Military images account for about three-fourths of the total, while non-military images account for the remainder. In the sections below, I briefly describe the most common visual frames along with key the pictorial conventions that Daesh photographers utilized.

Daesh media imagery by type

Military

Combat and war spoils were the two most recurring visual frames. The former depicted Daesh militants setting out on suicide missions or in battle shooting, sniping, and firing rockets at Iraqi or Peshmerga forces. The latter also included photos of militants confiscating enemy weapons and belongings after battle. Combat and war spoils imagery significantly dropped from November and December to January as the group was losing its grip on east Mosul. Over 70% of low-angle shots in the overall collection appeared in combat images, looking up to Daesh militants in battle—a visual technique known to convey the symbolic power of the photo subject(s).5 By contrast, over one-third of all high-angle shots appeared in war spoils images, looking down on confiscated belongings to indicate the enemy's loss and inferiority. Moreover, over half of all subjective shots appeared in these two frames, ranging from point-of-view to over-the-shoulder shots, hence embedding the viewer in the militant’s position as he fights with, snipes at, and walks over the bodies of Iraqi soldiers. These subjective perspectives are also employed to document the confiscation of the defeated soldiers’ belongings. Subjective shots are commonly used in first-person shooter games to promote viewer identification, prompt arousal responses, and foster presence in the scene. By plagiarizing from eminent popular culture images, Daesh targets youth by presenting its messaging in familiar, attractive visual tropes that stimulate embodiment and suggest perceptual alignment through a safe and virtual experience of action on the battlefield.

Eulogy images depicted Daesh “martyrs” before setting on suicide operations and they were often followed by long shots of explosions signalling the outcome. As the total liberation of east Mosul was in sight, eulogy images nearly doubled from November and December to January unlike the decreasing combat and war spoils images. Almost 90% of all instances of direct eye contact appeared in eulogy images, a visual technique often used to establish imaginary connection between photo subjects and the viewer by communicating what the former demands from the latter.6 This demand can be deciphered by examining the surrounding context, ranging from facial expressions, posture, and distance to other symbols. Eulogy images in Mosul typically position the militant at an intimate/personal distance (94%) with a confident smile (88%) to bolster the connection. The images show happy, confident, and determined young men—often pointing to the heavens signalling both monotheism and reward—who are engaging directly with the group’s supporters in demand of admiration, respect, and wishful identification. Taken together, Mosul eulogy images served as carriers of a trans-historical martyrdom narrative that transforms an on-ground defeat into a symbolic victory, guided by “a sovereign imaginary that demands death over disobedience.” By disseminating more eulogy images when facing direct blows, not only did Daesh reframe the battle, but it also attempted to boost its moral superiority among its followers online.

Daesh eulogy image

Non-Military

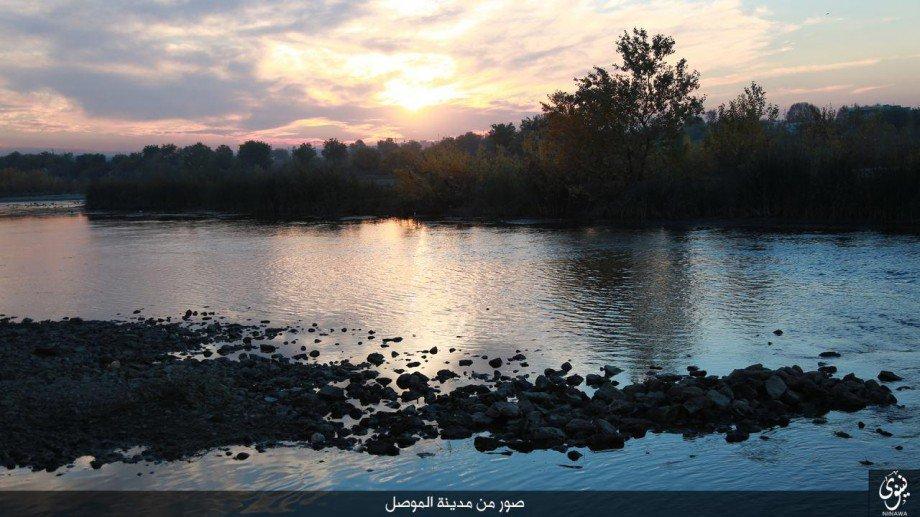

Non-military visual frames depicted the economy, social services, and urban and natural landscapes. Economy images presented Mosul as a prosperous city with vibrant markets, while social services highlighted service provision, such as electricity restoration, street cleaning, and education. These landscapes depicted the beauty and serenity of Mosul and the normalcy in its neighborhoods. Throughout the four-month period, one of these three visual frames appeared at least once daily. Mostly shot from a social/public distance, non-military images showed different types of scenes that were reportedly present in Mosul at the time. Taken together, scenes of prosperity, competence, and beauty aimed to give a sense of normalcy despite the ongoing battles.

Images of beauty and normalcy purporting to be Mosul & environs

The law enforcement visual frame portrayed the maintenance of order through hudud (punishments dictated by shari’a law) implementation and hisba (moral policing) activities. As the battle dragged on, law enforcement images doubled from December to January. The rise in law enforcement images suggests a sense of authority and control over the city as well as a commitment to implement shari’a law under any circumstances. Over 13% of all subjective shots appear in law enforcement images, embedding the viewer in the position of hisba agents reading the verdicts, punishing sinners, and destroying cigarettes and alcohol.

Hisba agent destroying a bottle of alcohol

What’s Next?

The battle over east Mosul showed that military pressure did not eliminate Daesh’s propaganda during the first four months. Whereas military pressure hindered the production and dissemination of some visual frames, such as combat and war spoils, the dissemination of other frames, such as eulogy and law enforcement, ramped up amid intensified pressure. Daesh utilized eulogy as a narrative of ultimate victory, bringing destruction to the enemy, and happiness to the “martyr” in this life and the hereafter. By doing so, Daesh abandoned any visualization of victimhood in favor of portraits of young and old men, willingly choosing to die, to exemplify the concepts of sacrifice, devotion, and courage to the group’s followers. With more eulogy and law enforcement images, the group attempted to remodel its visual sphere during battle by appropriating two of the most powerful interpretive constructs in Islamic discourse, martyrdom and shari’a implementation, in order to create a picture of an epic battle between good and evil.

The Mosul Operation posed a unique opportunity to gauge the extent to which Daesh could sustain a virtual warfare campaign under immense military pressure.

The social media battle will remain after Daesh loses its territories, and hence necessitates the development of nuanced and effective strategic communication campaigns in response. Although Daesh’s propaganda cannot be eliminated, its visual sphere can surely be disrupted and the underlying constructs rendering the group’s narrative powerful can be dismantled. Framing analysis allows us to understand the localized ingredients of Daesh’s visual sphere in which pictorial conventions constitute a powerful device to engage the viewer. By comparison, using Daesh’s own propaganda material and/or placing a talking head in front of the camera—whether a religious scholar or a grieving mother—puts counter-messaging campaigns at a disadvantage7 compared to the engaging visual narratives Daesh utilizes. To best counter Daesh’s narrative, a more compelling and convincing story has to be created, one that can get the target audience involved in an overarching metanarrative and engaged with the depicted characters, while encapsulating a clear call for alternative action rather than inaction. In the context of the Mosul battle alone, for example, hundreds of Daesh members not only bought into the group’s narrative, but also decided to take their own lives by reportedly conducting over 480 suicide operations. Until strategic communication campaigns can embody a powerful metanarrative to compete with Daesh’s visual sway over the eyeballs of those who consider joining the group and/or engaging in violent action in their home countries, such efforts will be less likely to succeed.

1 Milton’s (2016) “Communication Breakdown: Unraveling the Islamic State’s Media Efforts” and Zelin’s (2015) “Picture Or It Didn’t Happen : A Snapshot of the Islamic State’s Official Media Output.”

2 Kovacs’ (2015) “The “New Jihadists” and the Visual Turn from al-Qa’ida to ISIL/ISIS/Da’ish;” and Wignell, Kay, and Lange’s (2017) “A Mixed Methods Empirical Examination of Changes in Emphasis and Style in the Extremist Magazines Dabiq and Rumiyah.”

3 Winkler, Damanhoury, Dicker, and Lemieux’s (2016) “The Medium is Terrorism: Transformation of the About to Die Trope in Dabiq”

4 Damanhoury’s (2016) “The Daesh State: The Myth Turns into a Reality;” and Fahmy’s (2016) “What ISIS wants you to see”

5 Fahmy’s (2004) “Picturing Afghan Women: A Content Analysis of AP Wire Photographs During the Taliban Regime and after the Fall of the Taliban Regime;” and Mandell and Shaw’s (1973) “Judging people in the news-unconsciously: Effect of camera angle and bodily activity”

6 Kress and van Leeuwen’s (1996) “Reading images: The grammar of visual design”

7 See Think Again Turn Away. (2015). Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications: https://www.youtube.com/user/ThinkAgainTurnAway/videos; Mother Schools. (2016). Women Without Borders: http://www.women-without-borders.org/projects/underway/42/; and Stop Djihadisme. (2015). The National Center for the Prevention of Radicalization: http://www.stop-djihadisme.gouv.fr/