Keeping a Distance: ‘Bushman Tourism’ in Botswana

archive

walking with the San in the Kalahari (photo: Junko Maruyama)

Keeping a Distance: ‘Bushman Tourism’ in Botswana

The San or ‘Bushman’ are indigenous hunter-gatherers of southern Africa. The uniqueness of their lifestyle, culture, and language have long fascinated people around the world, but because of their distinctiveness from other African groups, they have been marginalized for a long time. Although their ‘exotic’ image has become globally recognizable through postcards, books, and movies since the beginning of colonization, until recently it has been difficult for tourists to visit San communities because of poor infrastructure and services in the areas they inhabit. Over the last twenty years, however, so-called ‘Bushman tourism’ has emerged in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. Growing numbers of international tourists visit the San to encounter their culture and lifestyle, and such tourism is expected to contribute to empowerment and the development of local minority communities such as the San. Yet even as they embrace some of the opportunities offered by tourism, the San also seek to maintain their cultural and economic autonomy in order to ensure that they don’t become too dependent on tourism.

As the United Nations has designated 2017 as the ‘International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development’, global awareness of sustainable tourism’s contribution to development has grown. In Africa, tourism is one of the fastest growing markets and there are high expectations that it not only contributes to economic development but also helps to empower marginalized populations, preserve their cultural heritage, and conserve the environment.1 Meanwhile, ethnic tourism has been criticized for being exploitative of those whose culture is on display. In particular, critics point out that in cases where locals have little or no controlling interest, tourism becomes contested, generating debates about cultural dispossession, expropriation, and intellectual property rights.2

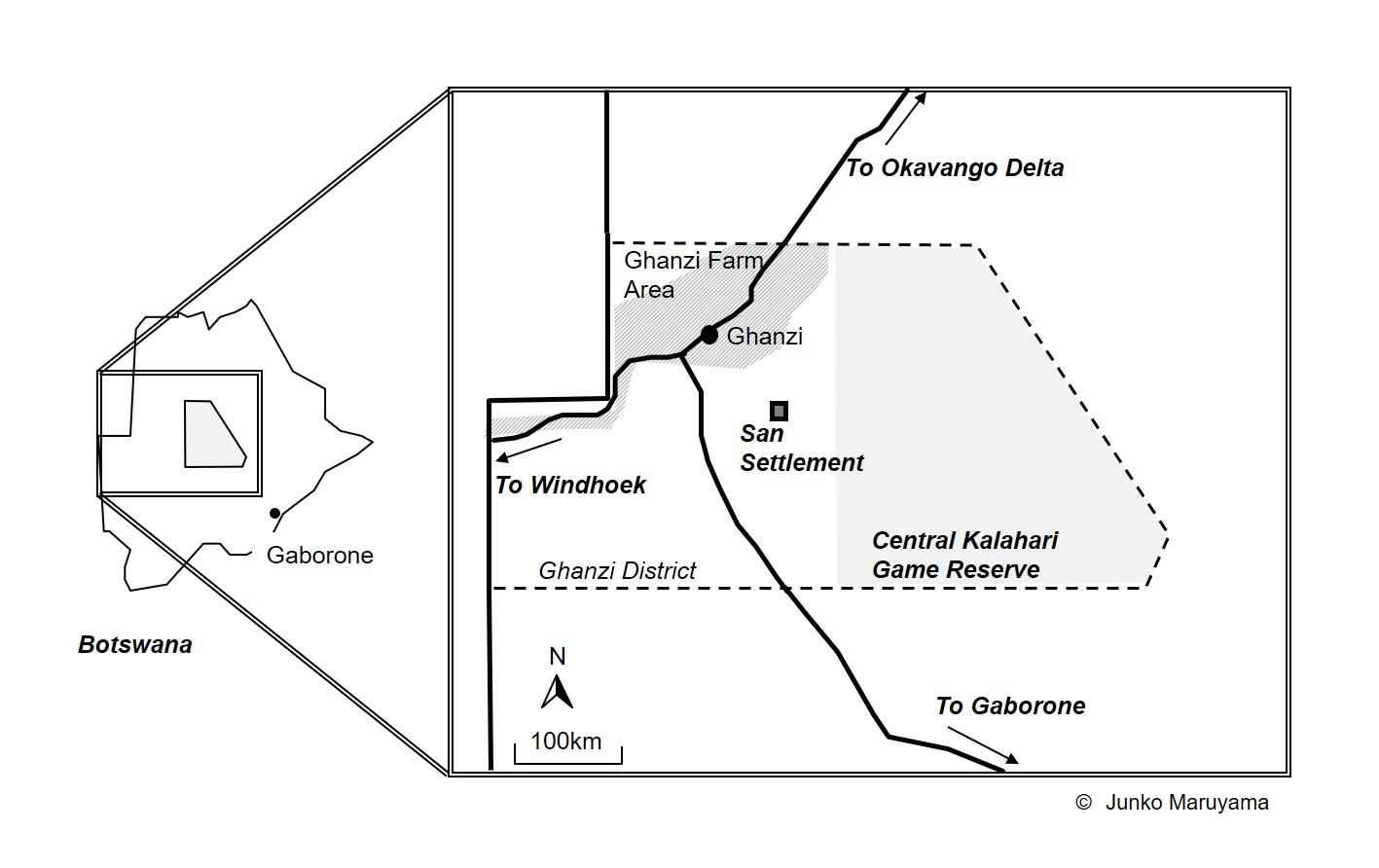

This article examines how the San in Botswana participate in ‘Bushman tourism’ and what its social and economic ramifications are for local San communities. Based on my long-term anthropological fieldwork in a San settlement in the Ghanzi District of Botswana between 2000 and 2017 (see Figure 1), and more recently (2015-2017) at a tourist lodge there, the essay presents detail on the historical background and current practice of ‘Bushman tourism’ and discusses possible desirable forms of San participation in the tourism sector.

Ghanzi as a site of ‘Bushman Tourism’

During the period between 2015-2017 there were around nine tourist lodges offering ‘Bushman tourism’ in Ghanzi and its surrounding area. Several local shops also sold San traditional crafts. Although half of the Ghanzi District is covered by the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, the town was just a small dusty locale in the remotest part of Botswana. Yet the situation changed drastically after 2000 with the paving of the road between Ghanzi and Maun, situated at the gateway to the Okavango Delta. With the improvement of infrastructure and services such as accommodations, supermarkets, and filling stations, Ghanzi has grown as an important stop-over for travellers along the main tourist route of southern Africa running from Cape Town to Victoria Falls via Windhoek (Namibia’s capital city), and to Botswana’s Okavango and Chobe National Park.

Figure 1: Map of the research site

Another important factor that has affected the growth of tourism is the ethnicity of local residents. The San comprise more than 45% of the population in the Ghanzi District3 and have played a major part in the development of ‘Bushman tourism’ there, while the other key player is the long-resident white farmer population of Ghanzi. Until the 19th Century, Ghanzi was primarily inhabited by the San, who had some interactions with surrounding areas. In 1894, under the Bechuanaland Protectorate Government, white settlers were allocated farm land and many San were displaced with some of them becoming low-paid farm workers.4 For several generations, the farmers’ main livelihood was cattle raising, but recently some have attempted to diversify by offering visitors a ‘Kalahari wilderness experience.’ Many have succeeded because they tap into social networks and business ties with travel agencies owned mainly by the white nationals of Botswana and South Africa. For Ghanzi’s white farmers, tourism has therefore become a reasonable business opportunity due to the improvement of the road between Ghanzi and Maun.

critics point out that in cases where locals have little or no controlling interest, tourism becomes contested, generating debates about cultural dispossession, expropriation, and intellectual property rights.

For the San, tourism can be an attractive option as well. Under recent government-led development programs and nature conservation policies, it has become more difficult for the San to continue their hunting-gathering lifestyle, which Botswana’s governing elite consider backward, inefficient, or environmentally destructive. Given this trend, many San are driven to find new sources of cash income, and others set up associations to improve their life conditions. For these individuals and organizations, tourism is expected to open a new door.

Working for ‘Bushman Tourism’

It was late in the afternoon. “Tourists are on their way…. here they come!” a young San lady called to her colleagues and quickly changed into her traditional skin clothes. She was working at one of the popular tourist lodges where I did my fieldwork. Most of the tour groups numbered 15 to 20 persons and arrived in big safari trucks, staying one night to enjoy ‘Bushman cultural activities.’ During the high season, two or three trucks arrive daily.

The main activities at this lodge are a ‘bush walk’ and ‘traditional dance.’ The San lady, together with eight colleagues, worked as bush walk guides and dancers. During the walk, they demonstrated their rich skills and knowledge of bush life, such as the uses of wild vegetables and herbal medicine, fire-making, and tracking animal footprints. After the walk, a traditional dance show was held around a fire, and then guests turned in for the night in traditional grass huts.

Tourists take photo of hunting demonstration by two young San (photo: Junko Maruyama)

In addition to being guides and dancers, some San work in this lodge as interpreters and as manager. The lodge was originally started by a local white farm owner who worked with an NGO to support the San way of life in Ghanzi. In 2000 he turned part of his farm, which had been in his family for generations, into a tourist lodge. After his passing several years ago, a San man was employed as manager, while ownership remains with the farmer’s family. Since that time the manager and his San colleagues have been able to control the decision-making process at the lodge and create their own tourist product (i.e. cultural activities).

The San staff mainly come from a government-planned settlement 80km away (Figure 1). They used to be engaged in hunting and gathering in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, but recently relocated to the settlement under a development program. In the settlement, some residents work as construction workers, earning about 540 pula (about $53) a month, while in this lodge the guide/dancer earns 2000 pula (about $195) or more depending on tips they receive; the manager himself earns even more.

Considering Sustainability

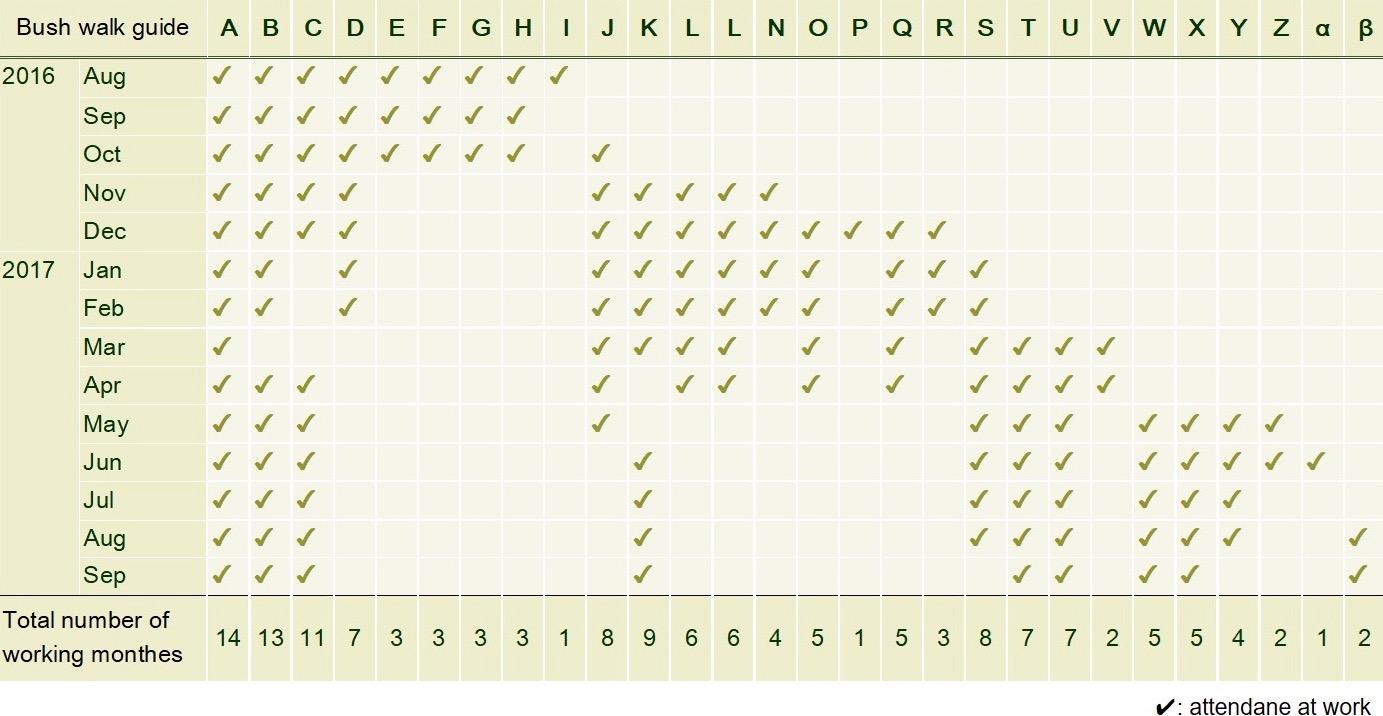

As we have seen from our example at one lodge in Ghanzi, the San earn relatively high incomes from tourism and retain control of tourism-related activities. The young San lady informed me that she likes to work in tourism because her culture is prized by tourists and the visitors bring her unfamiliar things. Even so, most of the San employees stop working after only a short time, as explained below.5 (Figure 2). Moreover, many of the staff’s relatives living in the settlement often visit the staff the lodge to work as day-laborers if jobs are available, while others may seize the opportunity to work as full-time guide or dancer when someone leaves. In this way, staff turnover is a common occurrence.

Figure 2: Attendance record of bush walk guides

From the above it may appear as if the San staff don’t take their jobs seriously. A report by the World Tourism Organization6 sees this unstable working style of the San as a cultural problem and suggests that it might be overcome through training. It is true that this San approach to work is sometimes incompatible with the goals of increasing both their earnings from, and their decision-making authority regarding, the tourism industry.

Interestingly, however, both the San staff and the owner family agreed that this working style is appropriate to the local situation. As they see it, tourism is an uncertain business. If incidents occur or illness breaks out, tourists stop visiting. For the San to secure a livelihood, it is prudent for them to take a side job in tourism and to maintain different livelihood strategies, including wage work, involvement in government-led development programs, and livestock farming and wild vegetable gathering. It’s also important to maintain active social networks among the San across greater Botswana and to share in the tourism-related job opportunities, albeit in limited ways, in order to mitigate the widening economic disparities within the San community.

New lifestyle at a San settlement (photo: Junko Maruyama)

As for sustainable tourism, the World Tourism Organization points out that sustainability principles refer not only to environmental aspects, but also to the economic and socio-cultural aspects of tourism development, such as respect for the social and cultural authenticity of host communities and economic longevity.7 For this kind of sustainable tourism, it should be important to respect the working style of the local community and their socio-historical context. Although tourism is beneficial and an enjoyable enterprise for the San, it isn’t everything. Remaining neither too close to nor too distant from tourism is their way to keep their autonomy and to avoid dependency on the global tourism industry.

1. Christie, I, Fernandes, E. Messerli, H. & Twining-Ward, L. (2014) Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods, World Bank, Washington, DC.

2. Butler, R., & Hinch, T. (2007) Tourism and indigenous peoples: Issues and implications. Routledge.

3. Cassidy, L., K. Good, I. Mazonde & R. Rivers. (2001) An Assessment of the Status of the San/Basawra in Botswana. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

4. Osaki, M. (2004) “Between white settler and Bushman” in Tanaka, J.et.al eds. Nomads。pp86-107. Kyoto: Showado

5. During my first research stay in 2015, there were nine bush walk guides, but a year later, six of them were new. According to a record of the attendance of the guides, only one had worked every month of the year while the others worked for a few months and left for the settlement or other places.

6. World Tourism Organization. (2003) Sustainable Development of Ecotourism: A Compilation of Good Practices in SMEs, World Tourism Organization Publications.

7. United Nations Environment Programme. (2005) Making tourism more sustainable: a guide for policy makers. World Tourism Organization Publications.