From Lotus Goddess to Holy Basil: Transnational Racio-scapes in US Presidential Politics

archive

Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, December 2014.

From Lotus Goddess to Holy Basil: Transnational Racio-scapes in US Presidential Politics

On June 27th, the night of the second Democratic primary debate, Donald Trump Jr. shared and deleted a tweet posted by the right-wing provocateur Ali Alexander. Alexander’s social media post alleged that presidential candidate Kamala Devi Harris was “not an American Black” because she was half Indian and half Jamaican. Trump Jr.’s spokesperson then offered a dubious defense of his boss claiming that he had not intended to endorse racism, but had simply been surprised to learn about Harris’s Indian background.1 What can we make of this controversy over Harris’s ethno-racial identity? How do we situate it within a broader context of resurgent nationalism in a country whose history is deeply saturated with transnational affinities, diasporic circulations, and cultural hybridities? We therefore wish to complicate projects of racial self-identification in US presidential politics by pushing back against the Black/White racial binary imposed on Kamala Harris and in doing so, to de-provincialize “studies of racial process.”2

We begin by noting that similar to Trump Jr.’s surprised reaction, some Indian American community groups have also been unaware of Harris’s Indian immigrant background and much more enamored of one of her Democratic Party competitors.3 Tulsi Gabbard, U.S. Representative for Hawaii's 2nd congressional district and a Hindu American of non-Indian ethnicity, has garnered more attention and raised three times as much money among Indian Americans as Harris—whose mother was actually an English-educated high-caste Indian woman.4 Clearly, Harris’s presidential currency has not registered strongly with this small but rather influential South Asian demographic, one of the most educated and wealthiest racial groups in the U.S.5 Although Harris has referenced her Indian background in different public platforms, she primarily identifies as African American with her official website stating that “she is the second African American woman in history to be elected to the U.S. Senate, and the first African American and first woman to serve as Attorney General of the state of California.” There is no mention here of her Indian ancestry, but in her 2019 children’s book Superheroes are Everywhere, she supplements her identification as African American with a brief note that she is also a “person of Indian descent.”

For us as Indian feminist scholars, it is intriguing to have two familiar Hindu Indian female names being tossed around in the U.S. media-sphere. Unlike Harris and Gabbard, prominent Indian American politician Bobby Jindal rarely uses his first name “Piyush” and former U.S. ambassador to the U.N., Nikki Haley, changed her first name from Namrata to Nikki. By comparison, Kamala Devi—meaning Lotus Goddess—and Tulsi—botanic nomenclature for holy basil—are names firmly ensconced within a sacred Hindu imagination and laced with ideological connotations that are illegible to members of most other ethnic and racial groups in the US. Taking into account global power relations and the influences of “gender, class, ethnicity, religion, labor, nationality, transnationality and politics”6 on US racial formation, we can see that the transnational racio-scape that scaffolds Harris and Gabbard in their bid for the presidential candidacy disturbs taken-for-granted and usually separated compartments of social identity.

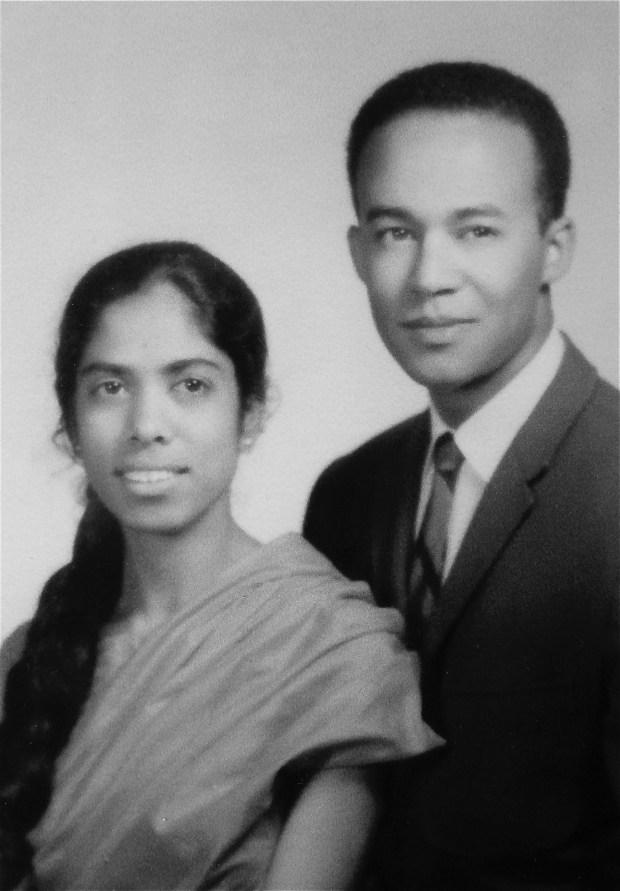

Kamala Harris credits her Indian mother, Shyamala Gopalan, for raising her with a strong sense of social justice and affiliation with the Black community.7 A politically aware and rebellious elite Tamil Brahmin graduate student who traveled from Chennai, India, to UC Berkeley in 1958, Gopalan—imbued with a rare political consciousness considering her roots—immersed herself in the student protests against the Vietnam War and participated in the civil rights movement, where she met and married Kamala’s father, a Black Jamaican immigrant student of economics. These postcolonial human flows with implications for race, class, caste, and gender shaped the circumstances of how Shyamala Gopalan and Donald Harris would have met at a US university campus, moving the nation’s demographic needle towards a society that would no longer be just white or Black, but instead a fluctuating demographic terrain of new ethno-racial self-identifications.8 Kamala Harris, contrary to Trump Jr.’s tweet, is thus Jamaican and Indian and African American.

Kamala Harris' parents, Shyamala Gopalan and Donald Harris. (Source: San Jose Mercury News)

Alliances between Black and brown immigrant communities, however, have always been tense, with anti-Black racism deeply embedded as well in sections of the Indian American community. Strikingly, illustrating racial solidarity with Black struggles and the agency involved in the social construction of race, Gopalan, a single mother by the time Kamala was seven, built a life for herself and her daughters that was anchored in close identification with Black communities. As Harris has emphasized, her mother “chose and was welcomed to and enveloped in the black community.”9 At the same time, the choice to cultivate close relations with the Black community did not mean an erasure of Gopalan’s Tamil Brahmin ethos. Performing an inter-racial/inter-cultural juggling act, Gopalan regularly took her daughters back to Tamil Nadu in India to connect with their grandparents and their South Indian cultural traditions. Harris’s recollections of her holidays in India with her Tamil Brahmin relatives are tinged with nostalgia and fondness for “South Indian culture and food.”10

What is less visible in Harris’s accounts of her Indian heritage is the immense Hindu caste privilege that is threaded through the needle of her biracial African American identity. Carrying their caste habitus (education, English-language skills, and social status) in their baggage, educated Hindu upper-caste Tamil Brahmin immigrants in the United States—continuing a longer history of urban migration within India—are part of the managerial professional class of Indian Americans,11 populating Silicon Valley, corporate management, universities, and journalism/media outlets. For example, Sundar Pichai (CEO of Google) and Indra Nooyi (former CEO of Pepsico) are both Tamil Brahmin Americans.

the transnational racio-scape that scaffolds Harris and Gabbard in their bid for the presidential candidacy disturbs taken-for-granted and usually separated compartments of social identity.

Such caste privilege, glossed over by Kamala and often by media profiles, gets lost in the broad references to her Indian background. A rare exception is a brief note in a San Francisco magazine profile, which quotes one of Harris’s friends saying that her Brahmin background might explain why Harris moved with confidence “around wealthy, powerful people.”12 Harris’s maternal Tamil Brahmin grandfather—with whom she interacted during her visits to Chennai—was a diplomat in the Indian government, and he had also been active in the fight to help India gain independence from British colonial rule. Such an elite upper-caste Tamil background blended with her maternal family’s activist consciousness and a more liberal outlook leavens Harris’s African American identity, shaped by her father’s Jamaican roots, mother’s parenting choices, her subsequent undergraduate education at Howard University, a Historically Black University (HBCU), and more.

Kamala Harris, official US Senate photo (Source: Wikimedia)

A light-skinned Kamala Harris’s Indian American side, including her Hindu ancestry, is also easy to miss. We could not locate a single image of her wearing traditional Indian clothing or the bindi (associated with Hindu women particularly) on her forehead. For many Indian Americans, including Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Christian Americans, religious identity shapes their ethno-racial identities, ranging from experiences of exclusion, discrimination, and community-building to support for conservative religious chauvinist movements in India. Aside from her Hindu first and middle names, Kamala Devi Harris does not come across as an explicitly Hindu Indian American woman. When asked if she would “wear a sari for her inauguration” on a book tour amidst a primarily Asian-American audience, Harris simply responded that she needed to win first before planning any celebrations.13

In contrast, Tulsi Gabbard—of Southeast Asian, French, German, and Polynesian descent (official website)—was hailed in 2013 as the first Hindu American politician in Congress and unique for taking the oath of office on a copy of the Bhagavad Gita (a Hindu religious text) instead of the Bible.14 Gabbard, often mis-identified as Indian American due to “her brown skin, black hair and Hindu name,”15 was exposed to Hinduism via the global flow of a particular sect, Gaudya Vaishnavism, also allegedly the basis of the Hare Krishna movement, which arrived in New York in 1965. Gabbard’s father, a practicing Catholic, encountered fragments of the Hare Krishna movement’s version of Hinduism in Hawaii as it got incorporated into The Science of Identity Foundation, a spiritual movement founded by Chris Butler. Gabbard’s website also notes that “her mother was born in Indiana and grew up in Michigan, was raised Methodist and later found her way to Hinduism.” Gabbard’s publicly proclaimed Hindu identity has facilitated connections with both Hindu Indian Americans and powerful Hindu right-wing nationalists in India. She has also empathized with Hindu Americans saying, “Hinduism is largely misunderstood today in part because of how it’s been portrayed in a negative and backwards way.”16 With no deep relationship to or lived experience in India nor any family connections, Gabbard has thus inserted herself into an Indian American ethno-racial formation through religion. An India Abroad article, published earlier this year, lays bare the messy and ill-defined contours of the Democratic primary’s racio-scape confronting some Indian American voters who may have to choose between “Tulsi or Kamala.”17

For many Indian Americans, including Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and Christian Americans, religious identity shapes their ethno-racial identities...

Should Harris act more Hindu? Should Gabbard build stronger ties to India that go beyond an allegiance to its dominant faith? We don’t care. The race/ethnicity authenticity game is not what we are invested in. We are instead delineating and unpacking the labyrinthine ways in which caste, class, postcolonial histories, embodiment, religion, and nation inform the social construction of race and its mediatized politics of visibility. In doing so, we aim to illuminate not only the political rhetorics of race at play in the U.S., but also in other countries—such as India, Turkey, and Israel—where similar dynamics of self-identification in electoral politics work to reduce, contain and conceal the messiness of transnational racio-scapes.

1. Katie Rogers and Maggie Haberman. “Donald Trump Jr. first shares, then deletes a tweet questioning Kamala Harris’s race.” The New York Times, June 28, 2019.

2. Kamari Clarke and Deborah Thomas. (2006). Globalization and race. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Page 9.

3. Kevin Sullivan. “I am who I am.” Washington Post, February 2, 2019.

4. “Tulsi Gabbard outraises Kamala Harris among Indian American donors.” The American Bazaar, June 23, 2019.

5. Suman Guha Mozumder. “Report: Indian Americans’ income highest in the U.S.” India Abroad, September 22, 2017.

6. Kamari Clarke and Deborah Thomas. (2006). Globalization and race. Page 9.

7. Kamala Harris. (2019). The truths we hold. New York: Penguin Press.

8. Lise Fundenberg. “The changing face of America.” National Geographic. October 2013.

9. Kamala Harris. (2019). The truths we hold. Page 9.

10. Shobha Warrier. “My niece, the U.S. senator.” Rediff.com. November 11, 2016.

11. C.J. Fuller and Haripriya Narasimhan. (2014). Tamil Brahmans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

12. Nina Martin. “Why Kamala matters?” San Francisco magazine, January 13, 2015.

13. “Will she wear a sari for her inauguration?” India Abroad, May 21, 2019.

14. Tanya Basu. “Hindus are thriving in America, but there’s only one in Congress.” The Atlantic, March 5, 2015.

15. Kelefa Sanneh. “What does Tulsi Gabbard believe?” The New Yorker, October 30, 2017.

16. Basu. “Hindus are thriving in America.”

17. Jagdish Patel. “Tulsi or Kamala?” India Abroad, January 30, 2019.