China and Nepal: Global Power in the Neighborhood

archive

China and Nepal: Global Power in the Neighborhood

Just three weeks before Chinese president Xi's message to the world that “socialism with Chinese Characteristics” was newly in the offing, Nepal's two largest communist parties, CPN-UML and CPN-Maoist, long divided and often antagonistic, forged an alliance on October 3, 2017 for the upcoming general election and echoed unequivocally “socialism with Nepali characteristics.” The two incidents encouraged observers in South Asia and beyond to scrutinize them for some underlying connection.

Political observers in New Delhi, the capital next door and key game changer in Nepal since the time of British rule, were bewildered by the sudden left-leaning political change. Indian Express inscribed an editorial entitled 'Red Card in Nepal' mentioning that Delhi suspected Chinese influence propelling the communist factions towards each other. Foreign diplomats in Kathmandu, including those of India, the USA, and the EU, were reported to be critical of the event, believing that the left alliance affects not only the emerging new democracy of Nepal but also India, clearing the field for communist China. At home, many in Kathmandu shared this view. The ruling Congress Party, the communists’ only rival, seems to be convinced that the unification would not have been possible without China's support. Some prominent civil society members have not been discounting China's expectation of the coming together of communist forces. And sympathizers believe that the communists, irrationally cornered by India and the ‘liberal West’, well deserve to get closer to China (Dixit, 2017).

The skeptics' assessments are not mere rhetoric.

During Nepal’s constitution drafting process in 2015, while China remained unmoved by its ‘peace and stability’ diplomacy, India advised leaders of all political parties in Kathmandu to sustain Hinduism as the state religion. Nevertheless, the communist-majority parliament declared the country a secular modern state, exacerbating India's hostility. It imposed an unofficial border blockade for almost five months. Facing a severe economic and humanitarian crisis, landlocked Nepal (also India-locked on three sides) turned to China for support. China whole-heartedly embraced Nepal's prime minister, the leader of the CPN-UML (who had earlier been close to India), and the countries signed historic trade and investment agreements. These were unprecedented in their diversification of Nepal-China trade and in ending the monopoly of the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC) over Nepal’s energy resources.

India lamented these actions publicly and diplomatically, but this increasingly cordial relationship between its two Asian neighbors to the north continued unstopped. China, earlier playing indoor diplomacy, now appeared proactive.1 Nepal too initiated an independent foreign policy. Despite India's resentment, Nepal subscribed to the One Belt and One Road (OBOR, now BRI) proposal of sustainable globalization and global connectivity. Notably it was the CPN-Maoist leader, then Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal 'Prachanda', who signed the document. More recently Nepal remained impartial during the 73-day face-off between the Indian and Chinese militaries in the Doklam Plateau, despite the fact that it had a 'Treaty of Peace and Friendship' with India which, for all practical purpose, is a security pact with the southern neighbor.

China's Growing Business

Nepal's economic ties with China had been loose for a long time. Prasad (2015) notes that Nepal’s trade with China was 1 percent in 1959/60,which increased to only 8 percent in 2001/02. It implies that India had long been Nepal’s sole business partner. Yet recently Nepal's commerce with China has outperformed trade with India. Tripathi (2016) shows that Nepal-China trade skyrocketed by more than 17 times since 2006. The doubling of the trade deficit between 2010/11 and 2014/15 also indicates that China's business in Nepal is expanding rapidly. Of $10 billion in total trade volume, Nepal’s share with China is currently 14 percent. Imports are consistently growing at a rate of 39 percent per annum.

...sympathizers believe that the communists, irrationally cornered by India and the ‘liberal West’, well deserve to get closer to China.

Business is expected to get a boost from the new policy outlook of the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its associated investment in infrastructure. China has been pledging that its support to Nepal would rise under the BRI. Sharing a 1400 km border along the Himalayan mountain range, Nepal has become a high priority of the project—especially considering that China's market connection to South Asia is easier via Nepal given its 1780 km open border with India's three populous states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal.

During the March 2017 post-earthquake investment summit in Kathmandu, representatives of 89 Chinese firms participated—the largest delegation of all—and committed $8.3 billion in investments in different sectors. The amount dwarfs India's commitment of $317 million by 21 participating firms. Nepal's traditional donors Japan and the UK each promised $1 billion while the United States pledged $500 million. The president of the Beijing-based Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) announced at the summit that Nepal would receive loans from the Bank starting in 2018. Notably, in 2015/16, China’s FDI share was 42 percent of total FDI Nepal received from all sources in that fiscal year.2

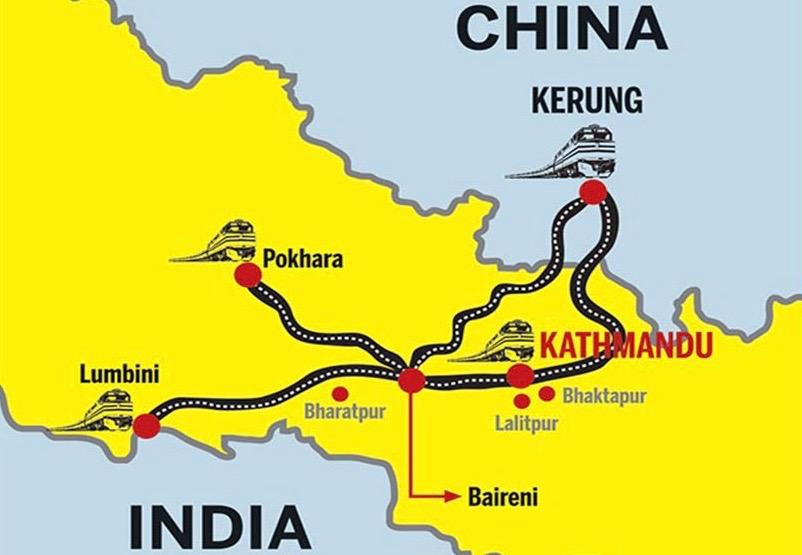

proposed rail lines link Kerung in Tibet through Kathmandu to Lumbini near the Nepalese border with India

Another independent source of $8 billion in funding comes with joining up the Kerung-Gyrung-Kathmandu-Pokhara-Lumbini railway. The network will connect China to India through Kathmandu. In 2007-08, China began construction of a 770 km railway connecting the Tibetan capital of Lhasa with the Nepali border town of Khasa, linking Nepal to Eurasian markets through China's national railway network. Upon completion, this connectivity would substantially reduce landlocked Nepal's dependence on Indian ports for access to international trade.

Currently, 108 Chinese companies are investing in different sectors including energy, services, tourism, agriculture, manufacturing, and mining. Two larger hydropower schemes, one international airport, two special economic zones, and a cross-border transmission line are other major areas of Chinese investment. It is estimated that these projects together have generated 32,932 jobs.

Business is expected to get a boost from the new policy outlook of the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its associated investment in infrastructure.

Soft-Power Dimensions

But the BRI projects entail more than infrastructure. Chinese soft power circulates via tourism, language, and culture as further avenues of connectivity. China ranks second after India as a source of tourists since 2010 according to Nepalese tourism statistics.3 Another example is the Mandarin language, which, until 2004, was taught at only one public campus of Tribhuvan University and another private campus in Kathmandu. In 2007 the Confucius Institute at Kathmandu University was founded, aimed at promoting Chinese culture and language. Since then the number of Chinese language teaching centers in Kathmandu has been growing.4 Both public and private schools in the capital are including Mandarin in their courses since 2005,5 and parents are convinced that learning the Chinese language will enhance their children's ability to compete in a world where China is now dominating. Recently, undergraduate enthusiasm for learning Chinese has risen considerably given that the BRI brings with it graduate scholarships at reputed Chinese universities. Entrepreneurs in major tourist hubs such as Pokhara are taking Chinese language training, and, since February 2017, officials from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Education are learning Mandarin to enhance their understanding of China.6

Political connections

China's political connections to Nepal, however, have not been so smooth. India, as the “largest democracy,” often marginalizes “communist” China and many Nepali politicians have historically followed suit. A recent example was seen at the high-power BRI Conference in July 2017, where Nepal's Prime Minister at the time, Sher Bahadur Deuba—leader of center-right Nepali Congress party, known as pro-India since its formation back in 1946—suddenly canceled his participation, sending instead a delegation under the leadership of the Deputy Prime Minister of his coalition government, a high-rank CPN-Maoist leader. Notably, Indian premier Narendra Modi also turned a blind eye to the conference. To analysts in both Kathmandu and New Delhi, the two leaders were understood to have cordially acted in unison vis-a-vis Chinese affairs. With a Congress Prime Minister in the present government, Chinese officials in Beijing seem doubtful about Nepal's intention to implement BRI schemes.7 Hence, it may not be irrational for China to aspire to a softening political turn in Kathmandu.

Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping at BRICS-BIMSTEC Outreach summit in Goa, October 2016. Photo: AP

Whether or not China is involved in unifying the two big Nepalese communist parties, the alliance gives China a ray of hope. The two communist leaders have identified themselves as pro-China in recent years, often lamenting that they are subject to India's conspiracies.8 In 2015 Khadga Prasad Sharma Oli, the CPN-UML leader, turned to China for support of its resistance to India's unofficial border blockade. As Prime Minister he signed the historic trade and transit treaty with China, breaking India's monopoly over Nepali trade. It has been reported in Delhi and Kathmandu that India wants to stop him from coming to power so that Nepal's outreach to China can be restricted.9 The CPN-Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal 'Prachanda', who commanded a decade-long armed revolution 1996-2006, had vowed to scrap the Nepal-India Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1950 when he initiated the revolution in 1996. He was the Prime Minister who signed preliminary proposal on Belt and Road during his official visit to China back in 2015. Not least, Prachanda had also proposed a 'trilateral agreement' among China, Nepal, and India on connectivity issues during the BRICS-BIMSTEC Outreach Summit in Goa on 16 October 2016, to which president Xi gave a positive nod over India's reluctance. Indeed, China believes that Nepal can be a bridge between China and South Asia.

It All Depends!

On their unification day, Nepal’s two main communist leaders announced that they would form a strong communist party and unify other scattered communist fractions (communists in Nepal form about 60 percent of the total electorate). When they vowed a “new Nepal” and “socialism with Nepali Characteristics” as their principal goals, they echoed President Xi's recent pronouncements. This trend towards unification has paved a way for skeptics to hold the view that communists in Nepal see China as a “model of 21st century socialism.” Would this mutual “rejuvenation” of socialism in the Himalayan neighborhood bring global China into Nepal and then South Asia? Although many uncertainties remain, recent developments suggest that China’s influence has grown significantly over the past few years, signaling a very substantial shift in economic, political, and cultural relations in the region.

1 See online at: http://time.com/4270239/nepal-prime-minister-oli-visit-china-beijing-india/

2 These and other details about Nepal Investment Summit, 2017. Online at:

3 For latest information on tourist arrivals: http://www.myrepublica.com/news/24658/

4 Mr. M.S. Sharma, the finance manager at Universal Language and Computer Institute

50 percent. His institute alone registers 300-400 students a year. The stated reason

for learning Chinese is both academic and commercial. ULCI was the first institute in

Kathmandu to introduce the Chinese Proficiency Test (HSK) back in 2006. Samir

Shrestha, Managing Director of Cambridge Infotec (a study abroad consultancy), stated

that enrollment in Chinese language classes is higher after the border blockade and

the Nepal-China Trade and Treaty agreement in 2015. People engaged in import and

export business have the greatest interest in language acquisition.

5 Mr. Basanta Shrestha, an official coordinator between the Chinese Embassy and schools

there are seventy-two schools teaching the language successfully, and each year

at least three schools initiate the course. Both parents and students are interested in

learning Chinese. He opined that the expanding demand for Chinese language in

schools is that students learn the complex language more easily in school than when

they become adults. He also mentioned that students with Chinese language

competency have high chances of getting higher education scholarships in various

fields including medicine, engineering, and economics. According to Mr. Subash

Bhandari, Vice Principle of Valley View English School, which launched Chinese

language in 2005, five students who studied the language up to higher secondary

level in his school are completing medical degrees with full scholarships from the

different universities in China.

6 See online at: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2017-11/02/content_34014562.htm

7 Recently, Chinese Vice Premier Wang Yang visited Nepal's PM and requested with

under BRI. Republica Daily, August 17, 2017.

8 The CPN-UML leader, KP Sharma Oli, became the prime minister of coalition

parties. But he resigned as the major coalition partner CPN-Maoist ran against

him to join hands with Nepali Congress party. He blamed 'geopolitics' as the cause

of the failure of his government, referring to India, See for details:

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/25/world/asia/nepal-prime-minister-resig...

The CPN Maoist leader, Pushpa Kamal Dahal 'Prachanda' had become the first republican

attempted to sack then Army Chief but went unsuccessful. After the short stint of nine

months in the power, he resigned charging India as conspirator to his progressive

policies to democratize Nepal Army. See for details:

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/south-asia/nepal-prime-ministe...

9 See note 3 above.