Organized Abandonment in the Racialized City: The Case of Buenaventura, Colombia.

archive

Organized Abandonment in the Racialized City: The Case of Buenaventura, Colombia.

Buenaventura, located between the Western Cordillera and the Colombian Pacific Ocean, is one of the most extensive municipalities in the department of Valle del Cauca, covering approximately 6,078 km1, and one of the most populous in this region, with around 324,644 inhabitants. This territory can be understood as a “ciudad negra” (Black city) in a profound and structural sense: not only because over 80% of its population self-identifies as Black or Afro-Colombian, but also due to its genesis and historical trajectory marked by Afro-descendant settlement since the 17th century, when Spanish colonizers promoted a mining economy at the cost of enslaved labor (Aprile-Gniset, 1993).

This foundational violence is key. The process of wealth accumulation through the exploitation, violence, and torture inflicted upon Black bodies did not vanish with the formal abolition of slavery rather it has persisted, morphing into new forms across different historical moments. The continuity of this violence, adapted to the economic and political contexts of each era, constitutes a defining characteristic of the black cities along the Colombian Pacific coast, among which Buenaventura is a paradigmatic case.

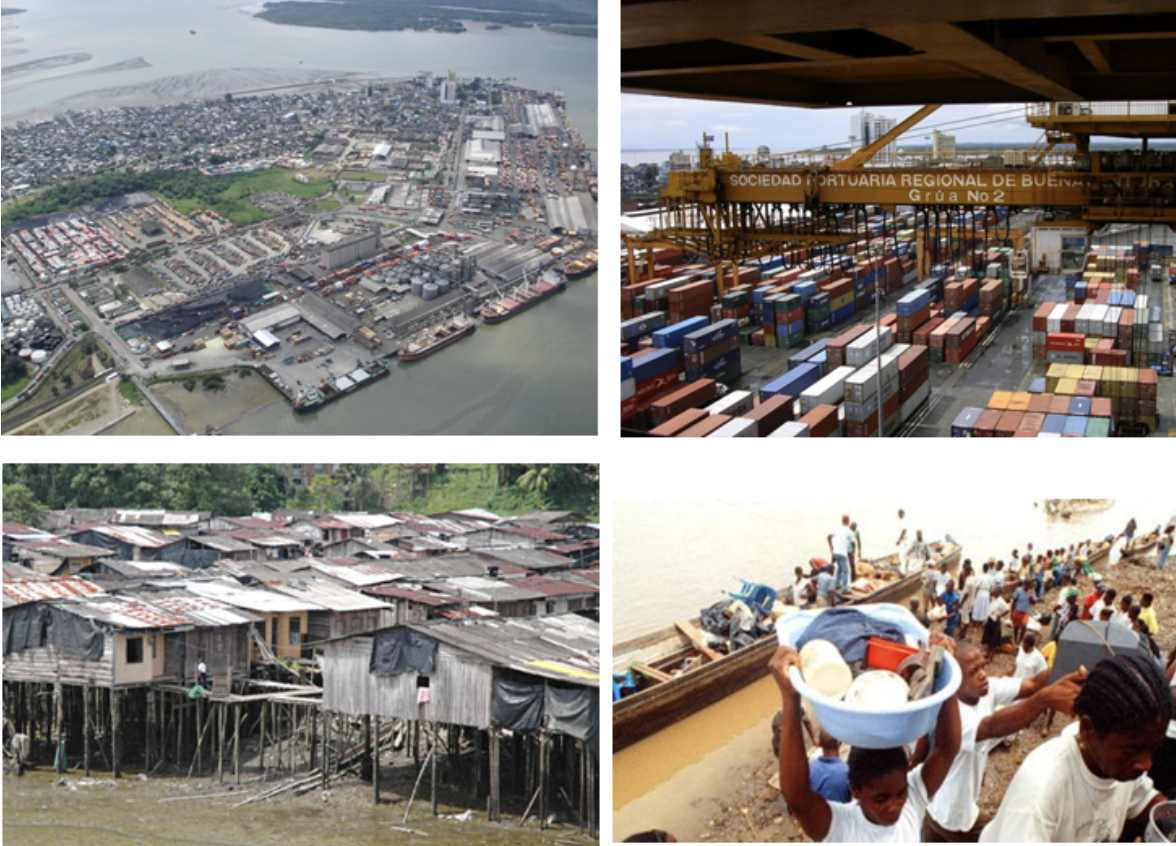

From a geostrategic perspective, the city holds a central place in the national economy: its port is the main node for Colombia's maritime trade, handling approximately 45% of the country's cargo1. This position makes Buenaventura one of the most crucial territorial entities for national wealth generation. In parallel, the city’s port sector generated USD 3.3 billion in tax revenues, positioning it as the third-highest revenue-generating city in Colombia in 20232. By contrast, the municipal budget for 2024 amounted to USD 207.8 million3, representing only approximately 6.3%, of the tax revenues generated locally. However, this economic centrality stands in brutal and sustained contrast to a local reality of widespread social precarity, historical state neglect, and high levels of violence that intensified dramatically from the early 2000s onward.

The rawness of this violence, both material and symbolic, broke into the national consciousness when the media began recording episodes of extreme brutality, particularly from the late 1990s through the early 2000s: unofficial curfews, restrictions on entering entire neighborhoods, forced disappearances, mass displacements, community confinement, systematic threats, selective assassinations, and recurrent massacres. Local residents usually deploy the saying “Hay males que duran más de cien años y cuerpos que los resistan” ("evils that last more than a hundred years and bodies that resist them") to underscore how the violence in Buenaventura was not an isolated or fleeting event, but the manifestation of a structural evilness, with deep historical roots notwithstanding their everyday resistance (Carabali and Silva, 2011).

This structural and ongoing violence was made visible during a field trip I conducted with students from a Colombian university back in 2010. What we found was a fragmented cityscape, permeated by a palpable, everyday fear, by internal displacement, and by an ironclad territorial control exercised by a multiplicity of armed actors including guerrillas, paramilitaries, and criminal gangs, who vied, and still vie, for strategic control of the port and the substantial illegal revenues associated with its operation.

Contrasts between the port and the community. | Photos from Observatorio del Pacífico.

This landscape of terror coexists, in an almost surreal manner, with an official and media discourse promising development and modernization: announcements of new deep-water ports, hotel projects, and expansions of logistical infrastructure (CONPES 3342, 2005). These were promises of progress that resonated as a hopeful echo in a city that consistently recorded one of the highest unemployment rates in the country. However, this narrative of the future clashed head-on with the immediate reality read in the headlines. For instance, while Colombia’s homicide rate was approximately 55.5 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004, Buenaventura’s rate reached nearly 100 per 100,000. Similarly, in 2006, the national displacement rate stood at around 966 per 100,000 people, whereas in Buenaventura it escalated to approximately 4,026 per 100,000 (Defensoría del Pueblo, 2016).

How is the antiblack violence of dispossession and death linked to the economic development of this port city? How has the complex web of violence in the city evolved? What real impact have massive investments in the port sector had on the living conditions of the local population, beyond macroeconomic figures?

The answers may be multiple, but one fact seems incontrovertible: the port economy has demonstrated an enormous capacity, almost an indifference, to operate and grow amidst the violence and human tragedy affecting thousands of the territory's inhabitants. From a reductionist, economic perspective, some would argue that the sector has generated employment and dynamism. However, a closer analysis of DANE data reveals a more nuanced truth: if in 2004 the unemployment rate was 28.8%, in subsequent years it remained stagnant in a critical range, between 24% and 27%. Beyond a slight decrease in the increase in tax revenues, fundamental doubts persist regarding the quality, stability, and equitable access to that employment, and regarding who the true beneficiaries are of this thriving economy that seems to float above the surrounding misery.

When this phenomenon is examined from a critical racial perspective, the inequalities become even clearer: Buenaventura's Black population disproportionately bears the weight of material and symbolic suffering. Premature death, explained by homicidal violence and, more structurally, by severe restrictions in access to basic conditions such as healthcare, food, and potable water that shorten life expectancy, primarily affects this community. Forced displacements, murders, disappearances, confinement, and daily precarity fall overwhelmingly upon Black bodies (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, 2015).

To understand this paradox of wealth and dispossession, it is useful to invoke the notion of "organized abandonment," as proposed by geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who argues that capital accumulation in certain spaces does not occur despite abandonment but because of it (Gilmore, 2007). It involves a systematic management in which certain populations are deliberately deemed expendable, relegated, and rendered vulnerable to facilitate resource extraction and surplus generation. In Buenaventura, I argue that the wealth generated by the port depends largely on maintaining structural conditions of precarity for the majority of its inhabitants. This mechanism allows the concentration and increase of profits among external actors, weakens social resistance, and turns corruption into one of the primary mechanisms for gaining a share of the profit pie. Any alternative for a more distributive or prosperous economic development for the local community thus appears less attainable.

It is undeniable that Buenaventura needs transformative investments that break the structural traps of poverty and create real conditions for improving income, well-being, and quality of life. However, the underlying, uncomfortable, and crucial question remains open: How much wealth does the city actually generate, and, above all, on what logic is it distributed, and for whose benefit? In Buenaventura, organized abandonment is not merely an unfortunate side effect but a necessary operational condition of the wealth-accumulation model that predominates in the city. Therefore, solving the city's structural problems necessarily entails challenging this model. It entails fairly redistributing the surpluses generated by its port activity and investing them in a prioritized and sustained manner in long-denied fundamental rights: a continuous and universal supply of potable water, dignified sewerage infrastructure, high-quality hospitals, universities, and research centers for robust socioeconomic development, and real economic opportunities with the effective participation of the local population. In other words, the distribution of the city's wealth can no longer operate under the extractive logic that has normalized tragedy. The human cost has been too high, and current living conditions constitute irrefutable evidence of an ethical and social failure that demands historical rectification.

The historical trajectory and contemporary reality of Buenaventura reveal a pattern that transcends the violent conjuncture or mere marginality. The city is not failing within the national economic model; on the contrary, it is fulfilling a precise function within it: that of an enclave based on accumulation by evisceration (Alves & Ravindran, 2020)

The promises of port modernization and macroeconomic growth indicators crash against the wall of stubborn evidence: the wealth flowing through its docks is sustained by the persistence of inhumane living conditions for the majority of its inhabitants. The paradox of being the gateway to national wealth and the epicenter of local precarity is not an accident, but the result of a logic that deems Black populations expendable to facilitate resource and surplus extraction.

Therefore, the central question of how to democratize access of Black dwellers to the city can no longer be solely how to generate more economic activity, but how the monumental wealth it already produces is distributed, and at what human cost. Any struggle for the right to the city demands a deliberate rupture with the historical cycle of abandonment. This entails, unavoidably, a radical and socially audited redistribution of port surpluses, aimed at guaranteeing, once and for all, the long-denied fundamental right to live.

1. For more information about port activities from Buenaventura, Colombia, see Zona Franca del Pacífico, "Puerto de Buenaventura líder en el Valle del Cauca para comercio internacional," https://www.zonafrancadelpacifico.com/es/puerto-buenaventura-ecoeficiente-valle-cauca-comercio-internacional/#:~:text=Puerto%20de%20Buenaventura%20líder%20en,posicionarse%20en%20el%20tercer%20lugar (accessed December 15, 2025).

1. Ministerio de Transporte de Colombia, "Competitividad en el puerto de Buenaventura," https://mintransporte.gov.co/publicaciones/8761/competitividad-en-el-puerto-de-buenaventura/#:~:text=Buenaventura%20es%20considerado%20el%20principal,el%2032%25%20del%20total%20nacional

2. For more information about tax revenue, see La República, "Estas son las regiones que más recaudaron impuestos para el año pasado," https://www.larepublica.co/economia/estas-son-las-regiones-que-mas-recaudo-de-impuestos-aportaron-para-el-ano-pasado-3827776

3. For more information about the budget for spending and investment in the city of Buenaventura, see Alcaldía Distrital de Buenaventura, "Presupuesto 2024," https://www.buenaventura.gov.co/images/multimedia/20241002_presupuesto_alcaldia_distrital_de_buenaventura___2024.pdf

Defensoría del Pueblo de Colombia. 2016. Problemática humanitaria en la región pacífica colombiana: Subregión Valle del Cauca – Buenaventura. Defensoría del Pueblo. https://publicaciones.defensoria.gov.co/desarrollo1/ABCD/bases/marc/documentos/textos/Problematica_humanitaria_en_la_Region_Pacifica_colombiana_-_subregion_Valle_del_Cauca_-_Buenaventura.pdf.

Jacques, Aprile Gniset. 1993. Poblamiento, habitats y pueblos del pacífico. Santiago de Cali: Centro Editorial Universidad del Valle.

Gilmore, R. W. 2007. Golden gulag: Prisons, surplus, crisis, and opposition in globalizing California. University of California Press.

Alves, J. A., and T. Ravindran. 2020. "Racial capitalism, the Free Trade Zone of Pacific Alliance, and Colombian utopic spatialities of antiblackness." ACME 19 (1). https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6pv7290p.

Carabali, Bladimir, and Laura Silva. 2011. Hay males que duran cien años y hay cuerpos que los resisten: el caso de Buenaventura. Febrero 1, 2011. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1954.7128.

Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica. 2015. Buenaventura: Un puerto sin comunidad. Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica. https://centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/micrositios/buenaventura/.